FREDERICK WARD

BUSHRANGER CAPTAIN THUNDERBOLT

Analysing the Evidence

and

Debunking the Myths

OTHER INFORMATION

Copyright Carol Baxter 2024

Bushranger Captain Thunderbolt

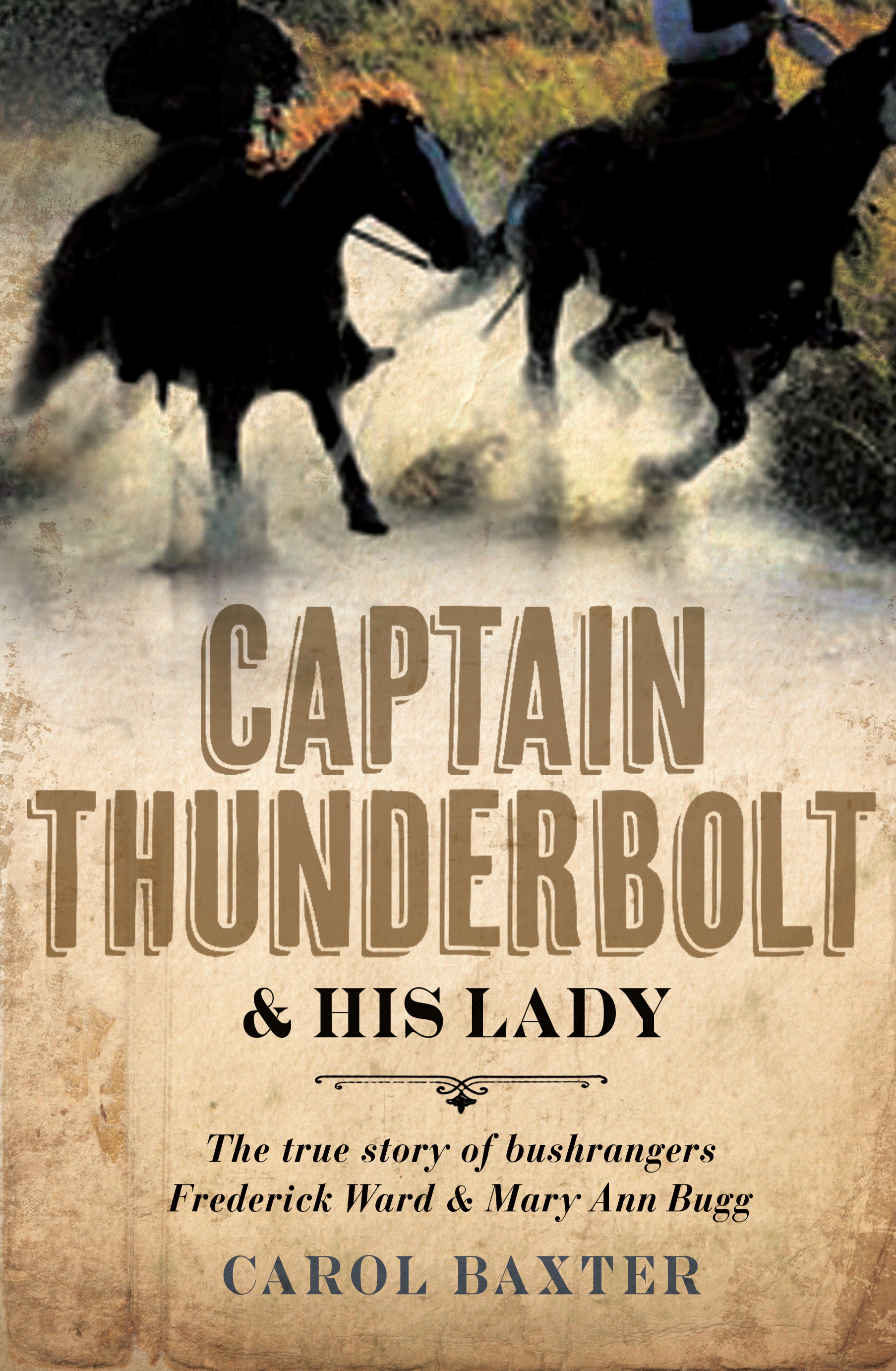

Carol Baxter is the author of the book, Captain Thunderbolt and His Lady: The true story of bushrangers Frederick Ward and Mary Ann Bugg (Allen & Unwin, 2011). It was published to critical acclaim and is being turned into a TV series.

While researching the lives of Fred and Mary Ann, Carol discovered that many of the claims made in books, articles and websites about them and their associates are wrong. To ensure that the correct information makes its way into the public arena, she analyses the evidence and debunks the myths about Fred and Mary Ann.

Topics covered below

- What punishments did Fred Ward receive on Cockatoo Island?

- Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?

- How did Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?

Topics covered on Carol Baxter's previous Thunderbolt website but not published here

Most of the spurious information about Fred Ward and Mary Ann Bugg was published on the website of a Ward descendant, Barry Sinclair. Now that his website is no longer accessible, there is less need to debunk its many error-ridden claims. Thus, the following analysis that was published on Carol's original Thunderbolt website has not been reproduced here.

- Did the death of Fred Ward's brother spawn his career in crime? (The answer is "no".)

- Did Fred Ward shoot at the police? (The answer is "yes, many times")

Links to additional information

What punishments did Frederick Ward receive on Cockatoo Island?

Many Thunderbolt books make astonishing claims about Fred Ward’s servitude on Cockatoo Island during the years 1856 to 1860 and 1861 to 1863, with some reporting frequent or extraordinarily long stints in the solitary confinement cells and even floggings. At best, these claims are based on anecdotes and gossip – perhaps even tall stories told by Fred himself. At worst, they are simply the imaginings of the author.

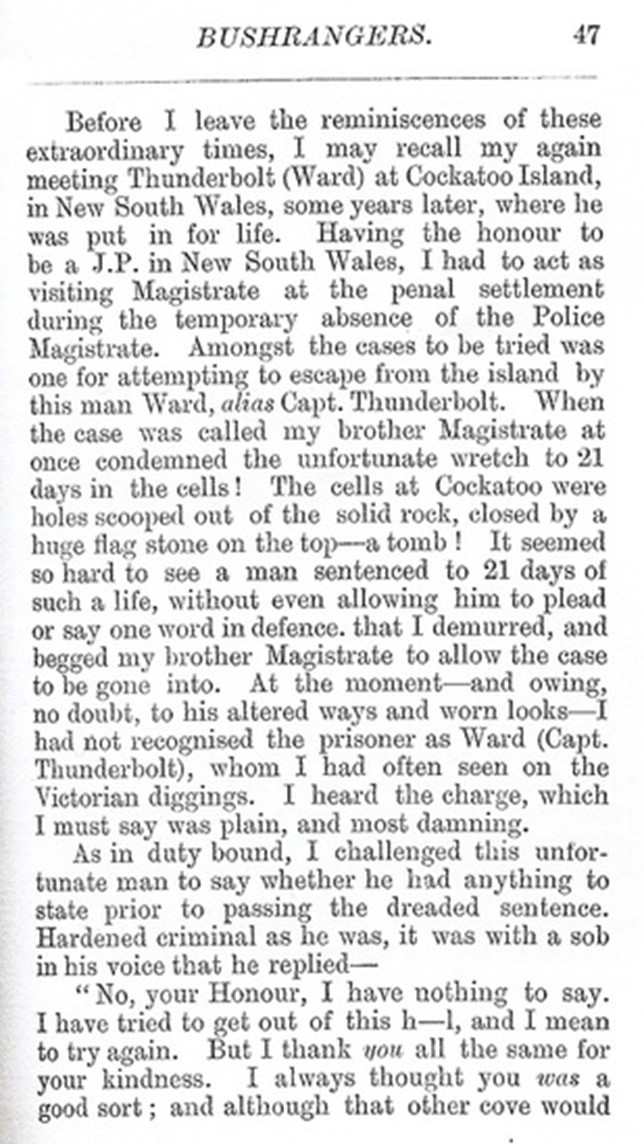

For example, most Thunderbolt books mention the claims made by Jules Joubert in his memoir, Shaving and Scrapes from many parts (see Image 1 and 2).[1] These were repeated in Bob Cummins' Thunderbolt who began by stating that "Visiting Magistrate Joules (sic) Joubert recollected a decision he adjudicated regarding an attempted escape by Ward".[2] Stephan Williams in A Ghost called Thunderbolt wrote that "a visiting police magistrate recalled seeing Ward being summarily committed to 21 days' solitary confinement for trying to escape".[3] Jim Hobden in Thunderbolt qualified his own version of the events by stating that "Ward's case was said to have attracted the attention of a French-born magistrate, Jules Joubert."[4]

So what did Joubert actually say? (See Images 1 and 2 on the right.)

Was Joubert telling the truth? The first detection strategy is to determine the likely accuracy of the unknown information – in this case, if Fred could have indeed been sentenced to 21 days in the cells by Joubert et al – by assessing the accuracy of the known information (I know I keep banging on about this simple rule of thumb, but if everyone followed this strategy to help them determine the truth regarding myths and secondary-source references, the Thunderbolt myths would not keep being repeated as facts).

What do we find? Joubert said: “I had not recognised the prisoner as Ward (Captain Thunderbolt), whom I had often seen on the Victorian diggings.”

The alarm bells should be ringing!

A few pages previously, Joubert had written: “For eight months I was hardly ever out of the saddle. During that time I experienced many adventures with men who since have either forfeited their life at the hands of the public hangman or served long sentences in H.M.’s gaol. Black Douglas, Thunderbolt, Donoghue, Gilbert, Ben Hall, and many other such celebrities have often been my fellow-travellers. Many a night have I spent at the camp-fire with such noted characters, yet have never been molested or stuck-up them.”[4a]

The alarm bells should be clanging!! Yes, Joubert was one of “those” people; that is, the men (and women) who claim to have important “friends” in a desperate attempt to seem important themselves. Joubert’s biography in the Australian Dictionary of Biography refers to him as an “adventurer and entrepreneur”. Evidently he was adventurous with the truth in addition to his other activities.

So what about his claims that Joubert attended Cockatoo Island as a magistrate and saw Fred sentenced to 21 days in the cells? I'll come back to that in a moment.

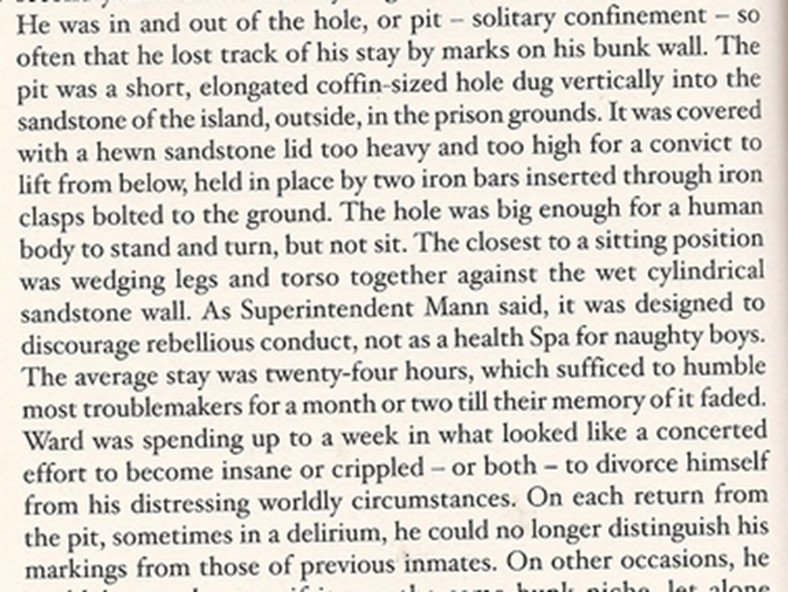

Another publication that makes noteworthy claims about Fred's punishments while on Cockatoo Island is the novel Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges? (See Image 3). While this is "fictional", the authors stridently claimed in the press that it is grounded in fact, so let's look at their statements about Fred's punishments on Cockatoo Island.

Regarding the solitary confinement cells, the authors wrote (see adjacent) that Fred spent so much time in the cells that he lost track of his stays, and that, while the average stay was 24 hours, he was spending up to a week each time.[5] The authors also state that Fred was strung up to the triangle and whipped fifty times because: "He needs to be reminded who's in charge here. He needs to have some respect."[6] They even intimated that he was raped.[6a]

One thing soon becomes obvious about the claims made by Joubert and the Scourge authors: they are not based upon any actual evidence. References to Cockatoo Island punishments have survived and these tell a completely different story about Fred’s servitude there.

First of all, let’s dismiss the claim that Fred was flogged. None of the prisoners were, by that time. Attitudes to punishment had changed. Flogging the mind (that is, solitary confinement) had replaced flogging the body.[7]

Secondly, the fact that the Scourge authors only intimated that Fred was raped when they boldly stated that he was flogged – even though the evidence shows quite the opposite – suggests that they knew they were on shaky ground with a rape claim!

Thirdly, the solitary confinement cells on Cockatoo Island bore little resemblance to those described by the authors of Scourge (see Earliest Convict Cells found on Cockatoo Island - no longer accessible).

Images 1 (above) and 2 (below)

Image 3 (above)

Now to Fred’s actual punishments.

In 1858, Fred petitioned the government for a conditional pardon. The authorities asked the Cockatoo Island superintendent for conduct details; he reported back that Fred had received a three-day stint in the solitary confinement cells for “neglect of duty as a Wardsman – being asleep at his post” on 20 October 1857. This punishment also added three days to the length of his sentence.[8]

Which raises an important point in itself. Under the regulations in force when Fred was convicted in 1856, every day he worked reduced his sentence by one-and-a-half days. Every day he spent in the cells not only meant that he was unable to reduce his sentence; it actually extended his sentence by the same amount of time.[7] Only a fool – or one incapable of controlling his own behaviour – would behave badly. Fred was no fool.

The Cockatoo Island Punishment Book has survived from 1859 onwards and records no further punishments prior to Fred’s receipt of a ticket-of-leave in mid-1860.[9] Tickets-of-leave were, of course, granted only to those who worked hard and behaved well, thereby reducing the amount of time they had to serve.[7] That Fred had indeed behaved well is also confirmed by the fact that he was assigned to the duty of “constable of the cells” – a responsible position – soon after his return to Cockatoo Island.[10]

So how do the Scourge authors account for Fred's receipt of such an indulgence when they state that he spent so much time in the cells he lost track of the days, etc, etc? They do so by stating that Minister Parkes intervened on his behalf![11] Confirmatory evidence? None.

In 1861, Fred’s ticket-of-leave was revoked and he was sentenced to serve the remainder of his first sentence plus an additional three years for possessing a stolen horse.[12] Changes in prison regulations meant that he would have to serve the full term of each sentence; no longer could a prisoner receive a remission for hard work and good behaviour.[7] The prisoners were angry about the regulatory changes. They rebelled in January 1863 and Fred was among them. While his resulting punishment was specified as “solitary confinement” – plus additional stints of “solitary confinement” when he refused to go back to work – there were not enough solitary confinement cells for all the rebels. Only the ringleaders were confined to the cells; the others were locked in a ward. Fred was ultimately confined to the ward for more than six weeks until he agreed to go back to work.[12]

Previously, on 6 May 1862, Fred had been confined to the cells at night for allegedly tampering with the cell locks while performing his duties as constable of the cells. The charges themselves seem suspect and his case was dismissed nine days later.[13]

Clearly, despite the claims made by writers trying to sensationalise Fred's story, Fred spent only a three-day stint in the solitary confinement cells in October 1857 for falling asleep on the job, between two and nine nights in the cells in May 1862 on charges that seem based more on malicious intent than illicit activity (hence their dismissal), and six-and-a-half weeks confined to a ward in January-February 1863 for refusing to work. These were his only punishments during his six years on Cockatoo Island.

The reality is that Fred was neither ill-behaved nor intransigent. During his first term of incarceration he was a model prisoner rewarded with a responsible position, whose only infraction was to fall asleep during night duty. During his second term of incarceration he became angry at the system and joined others in what was essentially a "strike". When that failed to achieve the desired end, he fled.

Fred's actual behaviour provides a more interesting insight into his character than the behaviour attributed to him in the sensationalised accounts.

Sources

[1] Joubert, Jules Shaving and Scrapes from distant parts, pp.47-8

[2] Cummins, Bob Thunderbolt, self-published, 1988, p.20

[3] Williams, Stephan A Ghost called Thunderbolt, Popinjay, 1987, p. 23

[4] Hobden, Jim Thunderbolt, self-published, 1987, p.10

[4a] Joubert, Jules Shaving and Scrapes from distant parts, p.41

[5] Hamilton, G. James with Sinclair, Barry Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges, Phoenix Press, 2009, p.78

[6] ibid, p.88

[6a] ibid, p.85

[7] Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly: Minutes of Evidence taken before the Select Committee on the Public Prisons in Sydney and Cumberland, 1861, Vol. 1, pp.1061-1282

[8] CSIL: Petition of Frederick Ward, 1858 [SRNSW ref: 4/549 Item 65/1712 No.58/1399]; CSIL: Convict Department to Principal Under-Secretary, 13 Jun 1860 [SRNSW ref: 4/3424 No.60/2462]

[9] Cockatoo Island – Punishment Book [SRNSW ref: 4/6502]; Ticket-of-Leave: Frederick Ward [SRNSW ref: 4/4233 No.60/28; Reel 893]

[10] Cockatoo Island - Daily State of the Establishment [SRNSW ref: 4/6505, 6 May 1862]

[11] Hamilton, G. James with Sinclair, Barry Thunderbolt: Scourge of the Ranges, Phoenix Press, 2009, pp.89-90

[12] See Thunderbolt Timelines

[13] Cockatoo Island - Punishment Book [SRNSW ref: 4/6502, 8 & 15 May 1862]; Cockatoo Island - Daily State of the Establishment [SRNSW ref: 4/6505, 6 May 1862]

Did Mary Ann Bugg help Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?

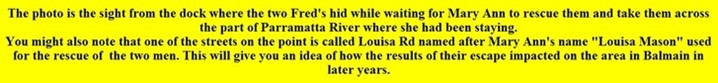

Most Thunderbolt books repeat the claim made by Inspector William Langworthy, as reported in MacLeod’s The Transformation of Menellai (1949), that Mary Ann Bugg helped Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island (see Image 1).[1]

A simple rule of thumb in historical research is to determine the likely accuracy of unknown information by determining the accuracy of verifiable information in the same source. The only prisoners on Cockatoo Island who wore irons at that time were those sentenced to do so – like Fred’s escapee partner, Frederick Britten (not mentioned, it must be noted, in MacLeod’s account). Fred Ward was not sentenced to wear irons, nor was he wearing them at the time of his escape. Therefore MacLeod’s account of Mary Ann’s involvement in Fred’s escape is clearly untrue.

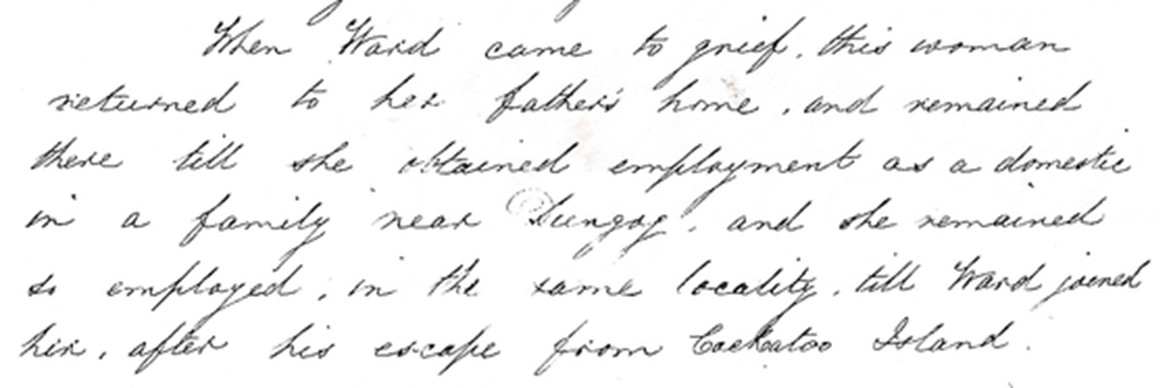

Was Mary Ann even in Sydney in 1863? Stroud Magistrate Thomas Nicholls reported to the Attorney-General in 1866 that he had known Mary Ann’s father for 30 years, that Mary Ann found employment in Dungog after "Ward came to grief" and that "she remained so employed [in Dungog] ... till Ward joined her after his escape from Cockatoo Island" (see Image 2).[2]

Was Nicholls telling the truth about having such knowledge of the Bugg family? Using the same rule of thumb mentioned above, we look into Nicholls' background and discover that he was born around 1804, just a few years after Mary Ann's father, and arrived with his wife and daughter as free passengers per the Waterloo in 1828. He was listed as a servant to the Australian Agricultural Company at Port Stephens when the Census was taken later that year (James Bugg was also employed by the A.A.Co in that district at that time). A respected man in the local community, Nicholls became a magistrate in 1858 and died at Stroud in 1878.[2a] Clearly, Nicholls did indeed have the personal knowledge of the Bugg family to provide this information.

Nicholls’ report had been requested because concerns about Mary Ann’s vagrancy conviction had been raised in Parliament. The report itself is a primary-source document from an independent and reliable source produced shortly after the events mentioned. By contrast, MacLeod’s account (in The Transformation of Menellai) is not only secondary-source (which in itself makes it less reliable), it is self-evidently third-hand information published nearly a century after the event.

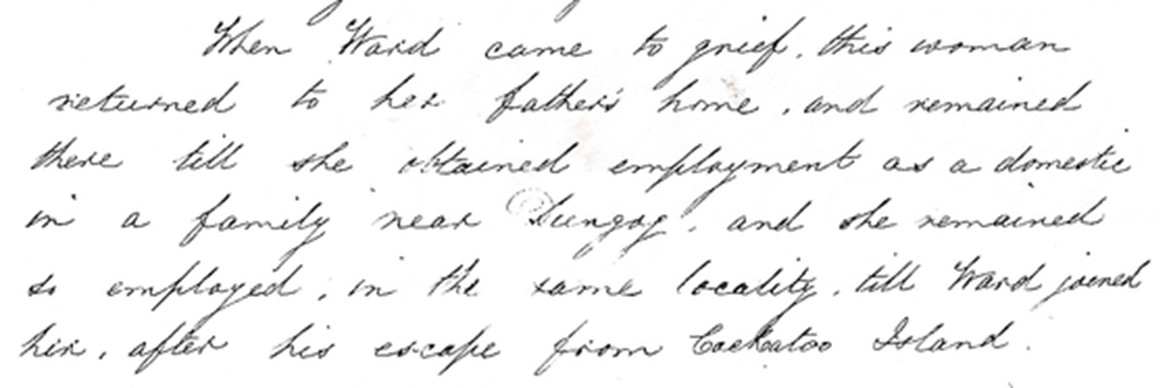

Nicholls’ statement about Mary Ann’s residence in Dungog between 1861 and 1863 is supported by contemporary newspaper accounts. A Dungog correspondent wrote in January 1864 that Fred Ward was in the district, and "he being previously married or living with a half-caste native-born in this district, it was but natural to suppose that he would make back to her" (see Image 3).[3]

A correspondent from Bandon Grove, not far from Dungog, wrote similarly (see Image 4).[4]

It is worth noting that Mary Ann's sister Eliza and her family were living at Main Creek at that time, and her father along the above-mentioned route.[5]

Clearly, Mary Ann was not living in Sydney in 1863. Rather, she was living and working in the Dungog district, as shown by these three primary-source references. Therefore, Mary Ann could not have helped Ward and Britten escape from Cockatoo Island.

So how did this claim arise? Interestingly, it is possible that MacLeod was repeating a story Mary Ann told him. Mary Ann seems to have liked intruding into the Thunderbolt narrative and, in particular, duping the police. The secret to a successful "tall tale" is to make it as accurate as possible, but Mary Ann's story – if she was indeed the source – contains too many errors to be believable.

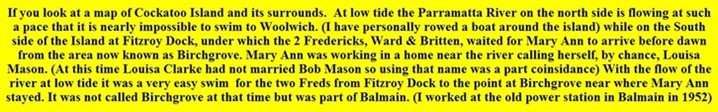

Despite the evidence showing that Mary Ann could not possibly have helped Fred escape from Cockatoo Island, these claims continue to be made. The latest is shown on the website of Thunderbolt aficionado, Barry Sinclair, who provides the information shown in Images 5 and 6.[6]

No evidence is provided here – or elsewhere – to show that Mary Ann worked in the Balmain district, or called herself Louisa Mason, or assisted the two prisoners to escape from Cockatoo Island. Nor was Louisa Street named as Sinclair claims. The Conservation Plan for Birchgrove Park provides the following information for "Louisa Road, Rose Street and Ferdinand Street", that "Joubert’s 1860 subdivision of the Birchgrove Estate created these roads. Louisa Street was laid out along the ridgeline of Long Nose Point to create the maximum number of allotments with deep water access, whilst not impinging on the grounds of Birch Grove House ... Today’s street pattern in Birchgrove was largely generated from what was proposed in this 1860 plan, with the streets named after members of the Joubert family."[7]

Not only is there no evidence whatsoever to support the claim that Mary Ann helped Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island, there is evidence from three independent and reliable sources showing that she was living north of the Hunter River during that period.

Image 5 (above) and Image (6) below

Sources

[1] Macleod, Alton Richmond The Transformation of Manellae: A History of Manilla, A.R. Macleod, Manilla, 1949, p.23,

[2] Colonial Secretary In-Letters: Magistrate Thomas Nicholls to Attorney General, 11 Apr 1866 [SRNSW 4/573 No.66/1844]

[2a] Sainty & Johnson, Census of NSW Nov 1828 Nos.N0301-4; Maitland Mercury 20 Apr 1858 p.2, 26 Jun 1873 p.1, 25 Jul 1878 p.1

[3] Maitland Mercury 21 Jan 1864 p.2

[4] Maitland Mercury 26 Jan 1864 p.2

[5] See the birth certificates of Eliza's children (see Mary Ann Bugg Timelines)

[6] Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady - sighted 30 Sep 2011 but no longer accessible

[http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Carol Baxter's Book.html]

[7] Conservation Plan for Birchgrove Park [http://www.leichhardt.nsw.gov.au/IgnitionSuite/uploads/docs/Birchgrove Park Conservation Management Plan - Part 1.pdf pp.9 & 27]

Image 1 (above) and Image 2 (below)

Image 3 (above) and Image 4 (below)

How did Fred Ward escape from Cockatoo Island?

From the evidence provided in the analysis above, it is clear that Mary Ann Bugg had no involvement in Fred Ward’s abscondment on 11 September 1863 or his subsequent escape from Cockatoo Island. Did anyone else help him and his accomplice, Fred Britten?

Letters to and from prisoners were read by the Cockatoo Island authorities who were also present during all prisoner visits. This made it extremely difficult for escape plans to be communicated by letter or in person, so it is not surprising that most escape attempts were either the product of spur-of-the-moment decisions based on unexpectedly fortuitous circumstances or were the product of plans that self-evidently originated on the island. Most focussed upon hiding on the island for an extended period of time, long enough that the authorities would give up the search and stand down the patrols, at which point the escapees would take to the water.

The Daily State of the Establishment reveals that Fred Ward had no visitors between his return to Cockatoo Island in 1861 and June 1863 when the register ends, whereas during his previous stint on Cockatoo Island he had received a number of visitors. Fred Britten received two visitors between February and June 1863: a John Ellis in March who was possibly a relative, and a ‘Mr Lane’ in May – probably a lawyer or government official as titles such as “Mr” were seemingly given only to official visitors to the island.[1]

Unfortunately, the Daily State of the Establishment volume covering the period from July 1863 to 1866 has not survived so visitor details cannot be determined. However, official correspondence makes no reference to possible external assistance, so it seems unlikely that anyone visited either of the men in the ten weeks prior to their escape. Otherwise the Superintendent would undoubtedly have requested that the authorities question these visitors.[2] For all of these reasons, it seems highly unlikely that Ward and Britten had outside help.

The pair evidently found an ideal hiding place and remained there for a couple of days. Later references to Fred’s escape (secondary-source references) mention his supposed hiding place. However, as these refer only to Fred himself and ignore the fact that he had a companion, doubts must arise as to whether these references are true. For example, Inspector Langworthy said that Mary Ann Bugg told him that Fred hid in a disused boiler.[3] But, since the other parts of this story are clearly untrue (see above analysis), we have to conclude that this entire claim is problematic, including the suggestion that Fred hid in a disused boiler.

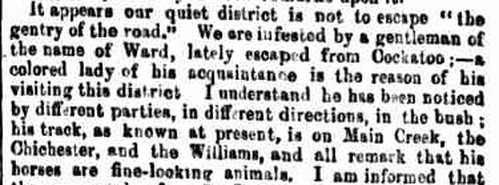

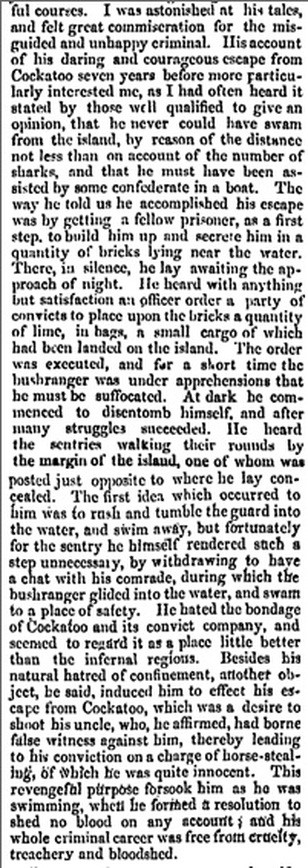

Another account of Fred’s escape was published in the Armidale Telegraph shortly after Fred’s demise (see Image 1).[4] These Recollections of Thunderbolt were provided by a bushman who had reportedly spent an evening in Fred’s company sometime previously. The stories recounted by the bushman distinctly resemble documented events involving Thunderbolt, yet with the slight differences that occur when a story has been embellished by the speaker and is being recounted at a later date by the listener. These slight differences, oddly enough, suggest that the bushman was telling the truth. Detectives know, for example, that if multiple witness accounts exactly match each other they are likely to be the product of “coaching”. Similarly, if the bushman’s stories exactly matched the newspaper reports they were likely to have been the result of study rather than conversation. If they bore no resemblance to other sources at all, they would be of doubtful authenticity because they could not be substantiated. So, before recounting the bushman’s story of Fred’s escape from Cockatoo Island, let us examine the other stories Fred reportedly told him (for the full article, see the relevant Trove online newspapers).

1. The bushman said that Fred talked about an encounter at the Rocks, at Uralla, “where the police, under Sergeant Granger, attacked him and his mate and wounded him”, and that “his horse got bogged and he limped away on foot, the police not daring to follow him”. False stories, like the claims that Fred escaped to America and died in Canada, rarely include specifics because these can be checked out. However the specificity of the name Sergeant Granger combined with the references to Fred having a companion at that time, his own wounding and the bogged horse all match the contemporary accounts.

2. Fred also reportedly mentioned that he had been “hard pressed at times, particularly on one occasion by a constable named Dalton, at Tamworth, who, he said, was a brave man”. Dalton was from the Tamworth police station and participated in the Millie gunfight in April 1865 when Fred’s young accomplice, John Thompson, was shot (see Thunderbolt Timelines for 1865 - First Gang). Dalton also nearly captured Fred and a later accomplice, Thomas Mason, in the Borah Ranges in August 1867 (see Thunderbolt Timelines for 1867), and a couple of weeks later the police forced Fred and his young companion to separate, leading to Mason’s apprehension. Dalton, of all the policemen on Fred’s tail, had nearly caught him twice, had shown his own bravery in the process, had wounded Thompson forcing Fred’s first gang to be disbanded, and had contributed to the break-up of his partnership with young Mason and the lad’s subsequent capture. That Fred should reportedly have commented on the activities and bravery of Dalton, of all policemen, strongly suggests that the bushman was repeating Fred’s comments. This is not the sort of thing that the ordinary person would remember simply from reading newspaper articles over a period of years (and old articles could not easily be checked in those days). Even I (having written about Thunderbolt) had to search for my references to Dalton to see why Fred would have commented on his endeavours. I discovered that he was indeed a policeman who was worthy of Fred’s praise.

3. Fred also told the story of “some gentleman in New England who had made a boast that he would shoot him the first time that he met him” and how he later met the man and introduced himself, and took the man’s revolver and gold watch, and the man was scared but Fred reassured him and rode many miles with him. This was almost certainly Magistrate Hugh Bryden of the Collarenebri district (rather than the New England district, one of the slight errors mentioned), whose encounters with Fred are covered in Captain Thunderbolt and his Lady (see also Thunderbolt Timelines for 1865).

4. Another story told how Fred and a young protégé stuck up a public-house. The innkeeper (whom he names Boniface) made a desperate leap and seized him by the arms preventing him from using his revolver, however the inn’s customers did not come to the man’s assistance. Fred called out to his accomplice to use his knife and “let his bowels out” and, seeing the unsheathed knife, the innkeeper released his hold and ran for shelter. Fred said that this was his narrowest escape from capture. Apart from the fact that the attacker was a customer named McInnes rather than the innkeeper (whose name was Simpson), the rest of the tale is true (see Thunderbolt Timelines for 1867 for sources). It was indeed Fred’s closest shave with capture. In fact, this story provides incredibly strong evidence that the bushman did indeed hear Fred's reminiscences. In reporting the Simpson robbery, the newspapers stated: "a person named McGuiness (sic) came in and seeing how matters stood seized Thunderbolt ... [and] from some cause not explained, the man who had hold of Thunderbolt immediately bolted". Many newspapers repeated this report but none provided any explanation for McInnes' sudden decision to bolt. However the depositions at Mason's committal late in 1867 provided the explanation. Victim Charles McKenzie swore under oath: "I saw a man named McInnes ... seize prisoner's companion [Ward] who then called out to the prisoner [Mason] to use his knife and rip McInnis' belly open." Mason pleaded guilty at his eventual trial so the witnesses did not testify. Accordingly it seems highly unlikely that these words were published in any press reports, so the only way the bushman could have known of the reason – and provided an almost verbatrim description of the dramatic words used – is if he heard it from someone with a personal knowledge of the event.

All of these stories are documented in contemporary records yet the bushman’s account contains the little errors that are found in second-hand repetitions at a later date. On the grounds that the likely accuracy of unverifiable information can be determined by the accuracy of verifiable information, all of these stories receive ticks suggesting the veracity of the man providing the Recollections. One can state with a high degree of certainty that the bushman did indeed meet Fred and that Fred did indeed recount his adventures.

This brings us to the bushman's statement regarding Fred's escape from Cockatoo Island.[4] The problem here is that the bushman doesn’t mention Britten. Could Ward and Britten have hidden in different places? This seems unlikely as they would have required two excellent hiding places. Many of the clever hiding places used by absconders existed only because of particular circumstances at the time – building operations, for example – and the non-transient hiding places were undoubtedly searched the next time an escape attempt was made. Moreover, if they had hidden in separate places, the odds of finding them would have doubled. If they had indeed found separate hiding places then they probably would have swum from the island at separate times. They were safer apart than together, so there would be no reason for them to try to meet up again at a later date. As it was, they apparently swam from the island together, journeyed to the New England district together, and separated two months after their escape.

What about the claim that a fellow prisoner built up a stack of bricks around Fred (or perhaps around both of them)? To do so, the prisoner would have had to use wooden beams to support the brick structure so that it wouldn’t fall on Fred. Hiding one man as they built such a stack would be difficult; hiding two men even more problematic. Could the story be true? The authenticity of the other stories suggests that this story could indeed be authentic – except for the fact that it only mentions Fred Ward and describes an unlikely hiding place. The jury is still out.

The story continued that Fred escaped the same night, whereas the evidence shows that the pair escaped two days after they absconded. But this is a minor error, the sort that could easily be made in a second-hand recounting of the story sometime afterwards.

Most Thunderbolt books claim that Ward and Britten swam to Balmain after escaping from the island. Yet, according to the Superintendent’s reports at the time of the escape, part of their clothing and Britten’s irons were found together, and some more of Britten's clothing in the water on the north side of the island opposite Woolwich. Upon this discovery, the superintendent immediately sent guards to the North Shore to search for them. The distance from the island’s north side to Woolwich was shorter than the distance from the south side to Balmain, Moreover, the night of the 13/14 September 1863 was starlit, and sentries were stationed around the island.[5] If the escapees entered the water on the north side of the island, as seems almost certain, why would they swim south to Balmain? To do so, they would need to swim half way around the island, risking being heard or seen, then across to Balmain. Moreover, such an extensive period in the water would have put them at greater risk of a shark attack and at the mercy of the tides and undercurrents. Alternatively, from the north side, they had only a short swim to the less-populated Woolwich area.

W.G. Small, a gaol superintendent at Berrima from 1861 to 1869, wrote in his reminiscences that an old lady who had once lived at Lane Cove told him that Ward arrived at her place and was so wet and cold that she took pity on him and supplied him with food and clothes but never told anyone for “fear of the consequences”.[6] This story seems feasible although it is again weakened by the fact that it makes no mention of Ward’s companion.

To date, all we know with certain about Ward and Britten’s escape is the following:

- That they absconded at the same time and from the same gang on the afternoon of 11 September 1863.

- That they probably hid together on the island.

- That they seemingly swam together from Cockatoo island on the night of 13/14 September 1863.

- That they seemingly swam north to Woolwich.

- That they headed north to the New England district, probably via the Gloucester district.

- That they were still together in the New England district in early November 1863.

- That they separated around mid-November 1863.

Perhaps with more newspapers becoming available online, we might one day discover more information about Ward and Britten's singular escape from Cockatoo Island.

Sources

[1] Cockatoo Island – Daily State of the Establishment, 1861-63 [SRNSW ref: 4/6505]

[2] Cockatoo Island – Letter Book: Re Ward & Britten [SRNSW 4/6518 pp.154-160]

[3] Macleod, Alton Richmond The Transformation of Manellae: A History of Manilla, A.R. Macleod, Manilla, 1949, p.23

[4] Recollections of Thunderbolt originally published in Armidale Telegraph and repeated in Argus 24 Aug 1870 p.7; the above photocopy is taken from West Coast Times, 28 Sep 1870 p.3 (a New Zealand paper that laid out the whole Cockatoo Island section in the one column)

[5] Cockatoo Island – Letter Book: Re Ward & Britten [SRNSW ref: 4/6518 pp.154-160]

[6] Small, W.G. Reminiscences of Gaol Life at Berrima, A.K Murray & Co, Paddington (NSW), c1923, p.6