MARY ANN BUGG

Analysing the Evidence

and

Debunking the Myths

DEATH INFORMATION

Copyright Carol Baxter 2011

Carol Baxter is the author of the book, Captain Thunderbolt and His Lady: The true story of bushrangers Frederick Ward and Mary Ann Bugg (Allen & Unwin, 2011). It was published to critical acclaim and is being turned into a TV series.

While researching the lives of Fred and Mary Ann, Carol discovered that many of the claims made in books, articles and websites about them and their associates are wrong. To ensure that the correct information makes its way into the public arena, she analyses the evidence and debunks the myths about Mary Ann.

Topics covered below

- Did Mary Ann Bugg die in 1867?

- When did Mary Ann Bugg die?

- Did Mary Ann Bugg have tuberculosis?

- Who was Louisa Mason?

- Was Yellow Long one of Mary Ann Bugg's nicknames?

Links to additional information

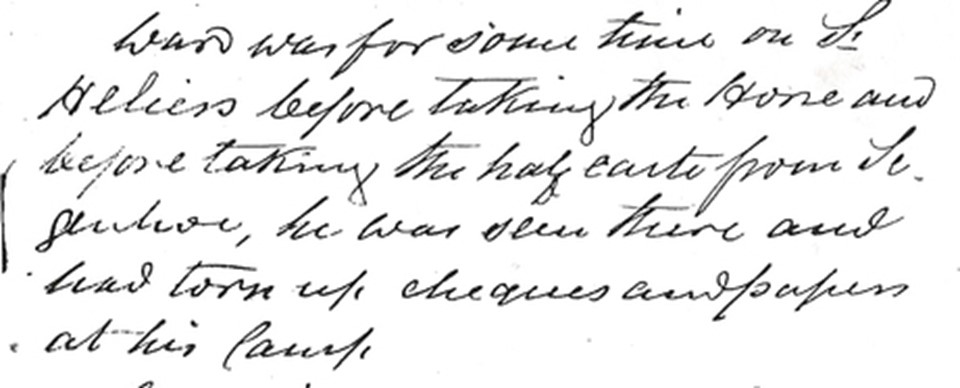

Determining Mary Ann Bugg’s life story has largely pivoted around one event: whether she did or did not die in November 1867. Most Thunderbolt publications claim that she did die in 1867, as shown below:[1]

Let's assess the actual evidence.

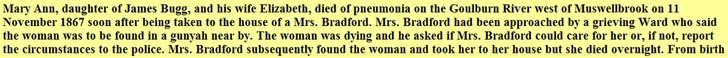

On 30 November 1867, John H. Keys wrote to the Superintendent of Police about the police’s failure to capture Thunderbolt while he was in the local area. With regard to the woman who had died at the Goulburn River on 24 November (not 11 November as stated above), Keys said: “Ward was for some time on St Heliers before taking the horse and before taking the half-caste from Segenhoe” (see Image 2).[2]

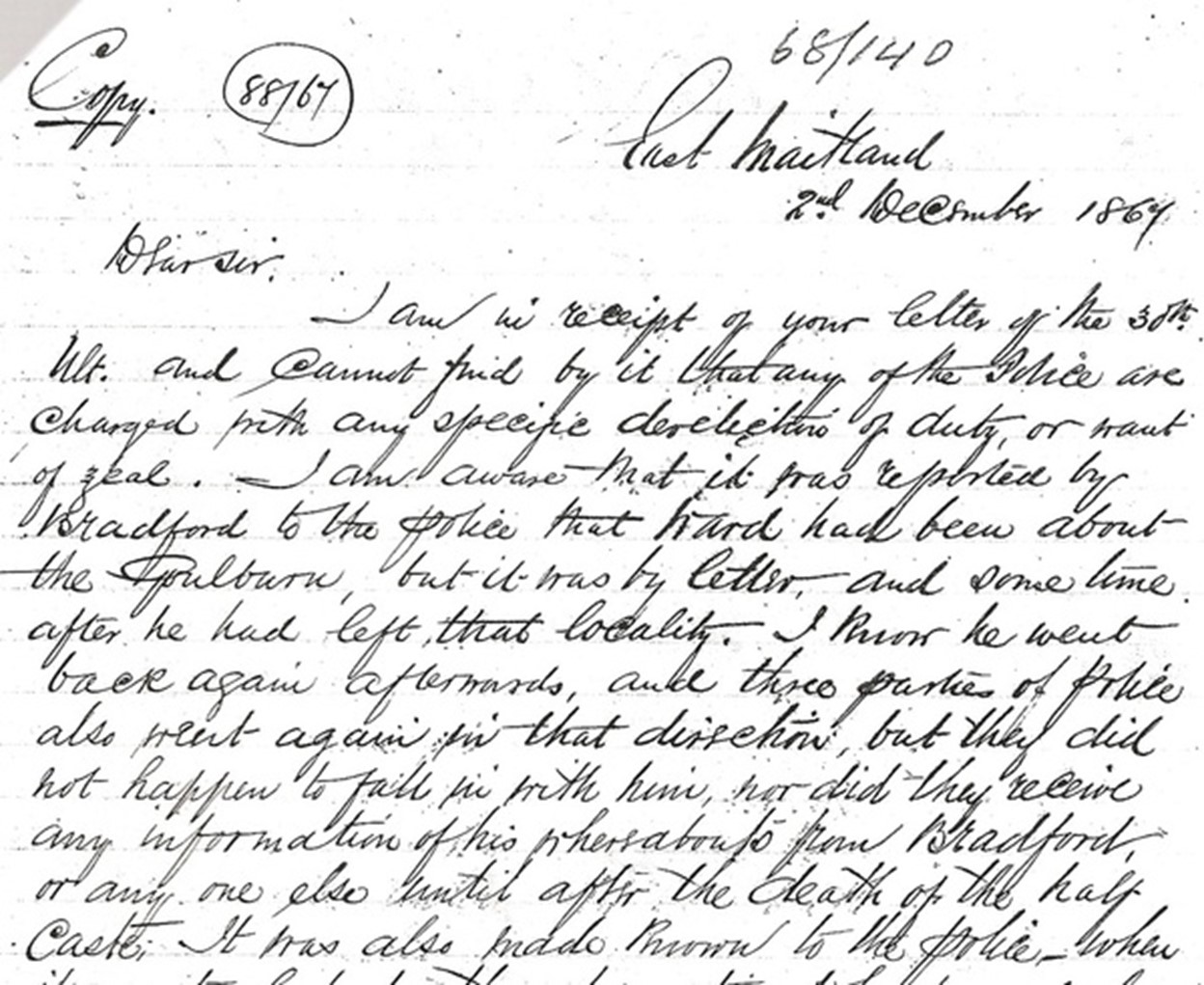

On 2 December 1867, Police Superintendent Morisset replied to Keys’ letter, remarking that the information about the Thunderbolt sightings was not received “until after the death of the half-caste” (see Image 3).[3]

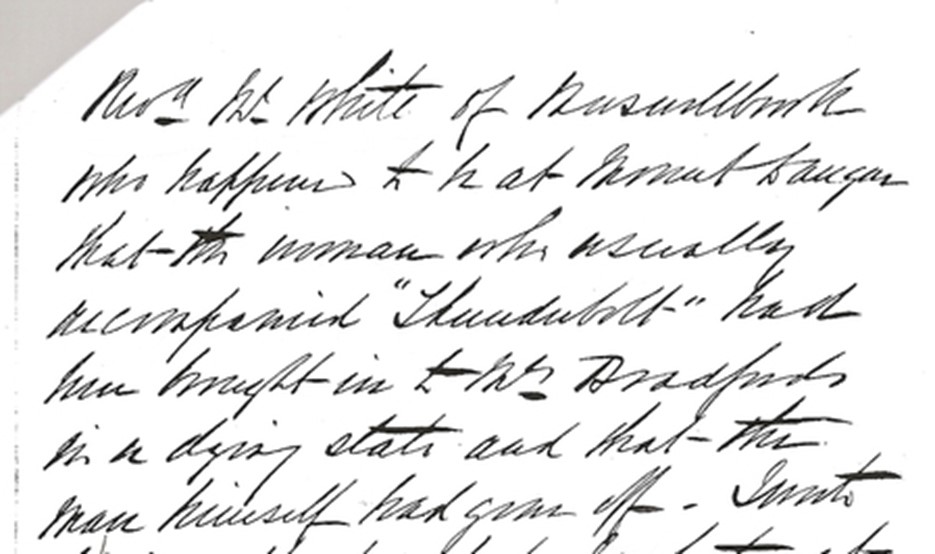

On 5 December 1867, Parliamentarian James White wrote a memo about the Thunderbolt sightings in the district. He mentioned that “the woman who usually accompanied Thunderbolt had been brought in to Mrs Bradford’s in a dying state” (see Image 4).[4]

None of these sources named the dead woman, merely referring to her as the "half-caste" or as Thunderbolt's woman. Yet most Thunderbolt writers have concluded that these references to the "half-caste" were references to Mary Ann Bugg. Such a conclusion seems surprising in view of the associated newspaper reports.

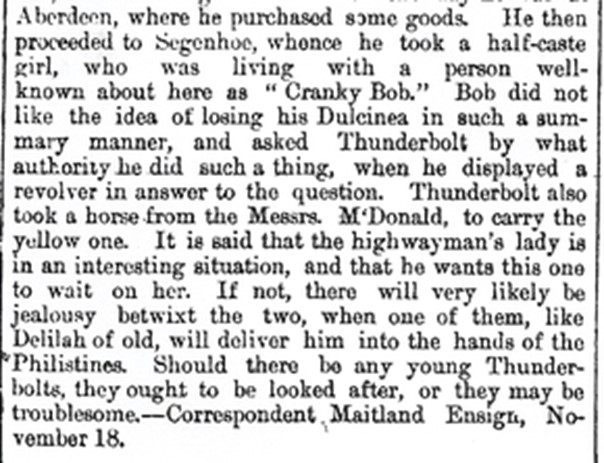

On 18 November, a correspondent for the Maitland Ensign wrote that Thunderbolt “then proceeded to Segenhoe whence he took a half-caste girl who was living with a person well-known about here as Cranky Bob ... It is said that the highwayman’s lady is in an interesting situation [pregnant] and that he wants this one to wait on her (see Image 5):[5]

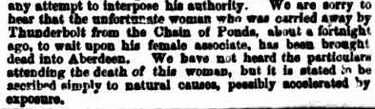

A short time later, the Singleton Times wrote: “We are sorry to hear that the unfortunate woman who was carried away by Thunderbolt from the Chain of Ponds about a fortnight ago to wait upon his female associate has been brought dead into Aberdeen.” (see Image 6). [6]

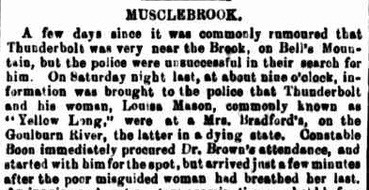

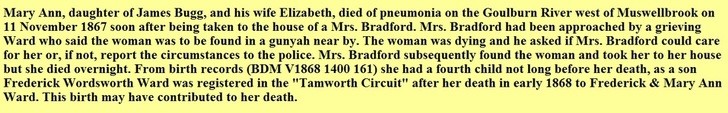

The Muswellbrook correspondent for the Maitland Mercury elaborated: “On Saturday night last [23 Nov 1867], at about nine o’clock, information was brought to the police that Thunderbolt and his woman, Louisa Mason, commonly known as ‘Yellow Long’, were at Mrs Bradford’s on the Goulburn River, the latter in a dying state. Constable Boon immediately procured Dr Brown’s attendance and started with him for the spot but arrived just a few minutes after the poor misguided woman had breathed her last” (see Image 7).[7]

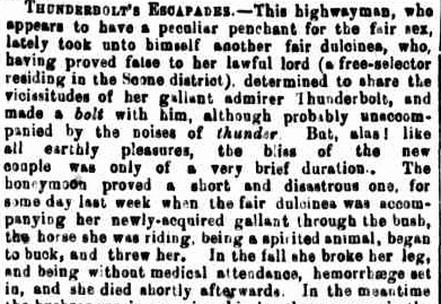

The Maitland Mercury pressmen provided their own facetious account of Thunderbolt’s amorous activities (see Image 8).[7]

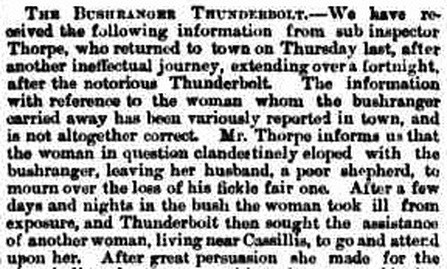

However, the Singleton Times advised that: “The information with reference to the woman whom the bushranger carried away has been variously reported in town and is not altogether correct. Mr Thorpe informs us that the woman in question clandestinely eloped with the bushranger, leaving her husband, a poor shepherd, to mourn over the loss of his fickle fair one. After a few days and nights in the bush, the woman took ill from exposure ... [and] was found in a dying state” (see Image 9).[8]

Not a single report named the dead woman as Mary Ann Bugg. In fact, two of them alluded to Mary Ann separately, suggesting that she was pregnant at the time and that Thunderbolt had brought the dead woman to assist her (quite clearly, he hadn't!).

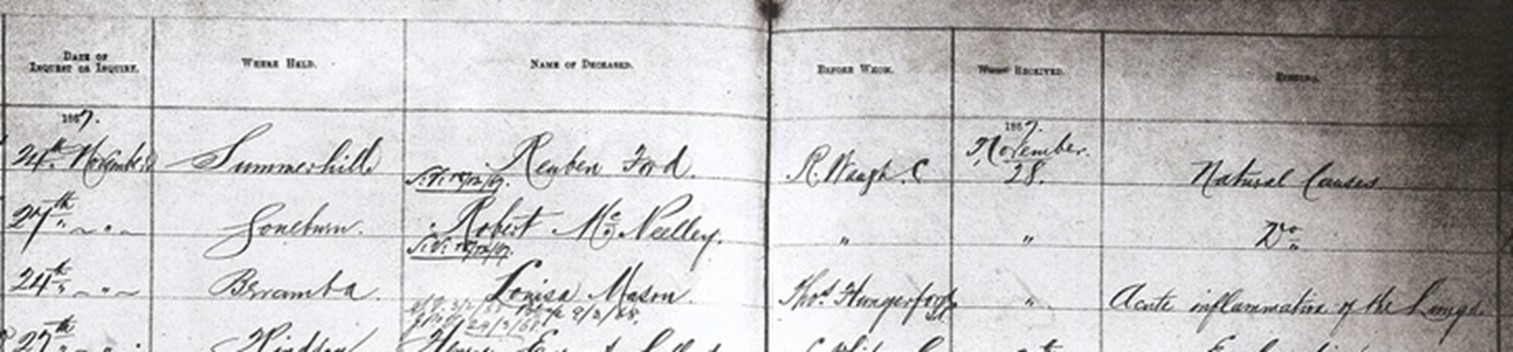

As it turns out, the official letters, memos and newspaper articles provided enough information to actually identify the dead woman. They revealed that she came from the Segenhoe/Scone district, was a “half-caste” named Louisa Mason or Yellow Long (the nickname itself suggesting Aboriginality), and was the wife of Cranky Bob. That the dead woman was indeed named Louisa Mason, not Mary Ann Bugg, is confirmed by her inquest report. The inquest of Louisa Mason was conducted by Thomas Hungerford JP on 24 November 1867 at Beramba (as mentioned also in the newspaper reports) and determined that she died from “acute inflammation of the lungs”.[9] Oddly, though, no death certificate exists in the records of the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages.[9a]

Civil records confirm Louisa Mason’s existence. At Muswellbrook on 13 August 1867, only a few months before her “elopement” with Thunderbolt, Louisa Jane Clark married Robert Michael Mason, a labourer from Rouchel near Scone (see Marriage Certificate).[10] This is clearly the Louisa Mason, wife of Bob of Scone, mentioned in the above newspaper reports. No children were registered as having been born to this couple, and the only Robert Mason listed as dying in the Muswellbrook district between 1867 and 1950 was a 32 year-old who died at Scone in 1874. No references to the remarriage or death of his wife, Louisa, have been found.[11]

Louisa Mason's Aboriginality would explain why the magistrate referred to her as the “half-caste” and why Parliamentarian James White assumed that the dead “half-caste” woman was “the woman who usually accompanied Thunderbolt”. White knew about Thunderbolt’s usual companion not simply from newspaper reports but because Mary Ann’s case had been brought before Parliament the previous year while he was a serving member.

Clearly, the evidence proves that the woman who died on 24 November 1867 at the Goulburn River was not Mary Ann Bugg but a different woman entirely named Louisa Mason. Evidently, all the historians who have claimed that Louisa Mason was Mary Ann Bugg – deciding that Louisa Mason must have been a nickname used by Mary Ann – have simply been repeating each other rather than returning to the original records and determining the truth for themselves.

Image 10

Sources

[1] Mary Ann Bugg - by Barry Sinclair (no longer available online) [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Mary Ann Bugg.html]

[2] John H. Keys to Superintendent of Police, 30 Nov 1867 [SRNSW ref: 4/616 No. 68/140]

[3] Superintendent Morisset to John H. Keys, 2 Dec 1867 [SRNSW ref: 4/616 No. 68/140]

[4] Memo of Parliamentarian James White, 5 Dec 1867 [SRNSW ref: 4/616 No. 68/140]

[5] Maitland Ensign quoted in The Empire 21 Nov 1867 p.8

[6] Singleton Times quoted in Sydney Morning Herald 28 Nov 1867 p.4

[7] Maitland Mercury 28 Nov 1867 p.4 (two articles)

[8] The Empire 11 Dec 1867 p.4

[9] Register of Coroner's Inquests and Magisterial Inquiries 1834-1942: Louisa Mason, 1867 [SRNSW ref: 4/6614 No. 939; Reel 2922]

[9a] An Registry experienced staff member undertook a thorough research but was unable to find any trace of the death certificate under the names Louisa Mason, Mary Ann Bugg/Baker/Ward, etc.

[10] Marriage Certificate: Robert Michael Mason & Louisa Jane Clark [RBDM ref: 1867/2545]

[11] NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages Online Indexes

Image 2 above and Image 3 below

Image 4 (above) and Image 5 (below)

Image 6 (above) and Image 7 (below)

Image 8 (above) and Image 9 (below)

When did Mary Ann Bugg die?

The woman described as “Thunderbolt’s half-caste”, who died in November 1867 at the Goulburn River in New South Wales, was not Mary Ann Bugg. Rather, it was a woman named Louisa Mason alias Yellow Long. Most Thunderbolt books claim that Louisa Mason was Mary Ann’s nickname although they provide no evidence to support the claim. Surviving records prove that Louisa Mason was a different woman entirely (see above).

In fact, Mary Ann Bugg could not possibly have died in November 1867. Proof is found in the birth of her son, Frederick Wordsworth Ward, in August 1868 at Carroll, NSW. Frederick's birth certificate lists his mother as Mary Ann Baker (which was Mary Ann Bugg’s legal name at that time) but the certificate omits any reference to his father.[1] His corresponding baptism entry, however, lists both parents: Frederick Wordsworth Ward and Mary Ann Ward.[2] These two independent primary-source records prove that the child Frederick was the son of bushranger Frederick Ward and Mary Ann Bugg.

Ever heard of a child in the 1800s being born nine months after its mother’s death? No? Exactly! Mary Ann Bugg could not possibly have died in November 1867. Yet these claims continue to be made, as shown below:[3]

The given-name combination Frederick Wordsworth is distinctive. The NSW Death Register indexes (available online) record only one man with these names dying between 1868 and 1979: Frederick Wordsworth Burrows, who died in 1937. A brother, Arthur Burrows, acted as the informant for Fred's death certificate and reported that Fred's parents were John Burrows and Mary Ann Boggs. What are the odds of two different men with the rare given name combination Frederick Wordsworth both having a mother whose name was, effectively, Mary Ann Bugg.[4]

Frederick Burrows himself acted as the informant for his mother’s death certificate in 1905. At first glance, the information he provided suggests that Mary Ann Boggs/Burrows was not Mary Ann Bugg. Frederick reported the following in that certificate:[5]

- That his mother was born in the Bay of Islands, New Zealand.

- That she was married twice: to Patrick McNally and to John Burrows.

- And that she had thirteen children to these two men.

Conversely, other sources regarding Thunderbolt's lover provide the following information about Mary Ann Bugg:

- That she was born in Gloucester, NSW.

- That she married Edmund Baker in 1848.

- That she had children fathered by Frederick Ward aka Captain Thunderbolt in the 1860s.[6]

However, at second glance, the similarities between the two women are striking:

- That both had mothers named Charlotte for whom no surname was known.

- That Mary Ann Burrows’ death certificate reported that she was born in New Zealand and came to Australia when aged about two, while her obituary noted that she was a “native of New Zealand and came to Port Stephens with her parents”.[7] Yet she herself reported in her son George's birth certificate in 1876 that she was born in Gloucester[8] (which in those days was in the Port Stephens' magistrate's district). This is where Mary Ann Bugg was born, according to her baptism and other family information.[9]

At second glance, however, the similarities between the two Mary Anns are striking:

- That Mary Ann Burrows was the exact age that Mary Ann Bugg would have been in April 1905.

- That Mary Ann Burrows’ son Frederick was the exact age that Mary Ann Bugg’s son Frederick would have been in April 1905.

- That both women had fathers named James Brigg(s) who worked as station overseers – Mary Ann Bugg’s father, of course, answered to Brigg throughout his convict servitude.

- That both women had mothers who were named Charlotte, with no surname known for either.

- That Mary Ann Burrows’ death certificate reported that she was born in New Zealand and came to Australia when aged about 2, while her obituary noted that she was a “native of New Zealand and came to Port Stephens with her parents”.[7] However Mary Ann Burrows herself reported in her son George's birth certificate in 1876 that she was born in Gloucester[8] (which in those days was in the Port Stephens' magistrate's district), where Mary Ann Bugg was also born.[9]

It is important to note that in the mid-1830s Gloucester was merely a sheep station employing convict shepherds. Children born in the district tended to be the product of liaisons between convicts and Aboriginal women. New Zealand similarly had only a small white population at that time, mainly missionaries and male convict escapees from Australia, so "white" children tended also to be the product of liaisons with Maori women. This suggests that Mary Ann Burrows had indigenous ancestry, whatever its nature.

It is also important to note that in the mid-late 1800s many Aboriginal people claimed New Zealand ancestry because Maori were treated with less contempt. Given these circumstances, it is more likely that Mary Ann Burrows was born in Gloucester, as she herself stated, rather than New Zealand, as stated by family members after her death. It is also more likely that any claim to Maori ancestry was a self-protective fiction. Indeed, multiple references have survived showing that Mary Ann Bugg herself claimed Maori rather than Aboriginal ancestry, including an article published in The Empire in 1865 reporting that "the captain [Thunderbolt] has a Maori as his gin".[9a] (see Birth Myths).

While an incredibly strong correlation clearly existed between the births and family backgrounds of the two Mary Anns, it was still necessary to link the two women in later life.

Mary Ann Burrows’ 1905 death certificate recorded that she married Patrick McNally when aged 16 (therefore around 1850) and that they had three children: Patrick, Mary A. and Ellen who were seemingly born in the 1850s. Mary Ann's obituary noted that she went to Bathurst in 1851 and subsequently to Mudgee, which suggests that her three McNally children were born in the Bathurst/Mudgee district.

Significantly, the Mudgee church registers record the baptisms of three children with almost identical given names — Mary Jane, Patrick Christopher and Ellen — who were born to James McNally/McAnaly and Mary Ann Baker between 1856 and March 1860.[10] Additionally, these children’s baptism entries reveal that they were illegitimate, indicating that James McNally and Mary Ann Baker were not married. They also reveal that James was a farmer at Cooyal in 1860, which is where Frederick Ward was residing when he met Mary Ann Bugg later that same year.[11]

So here we have three children listed on Mary Ann Burrows’ death certificate who were clearly born to a woman named Mary Ann Baker (which was Mary Ann Bugg’s legal name at that time). This woman was residing in the same vicinity as Mary Ann Bugg when she met Fred Ward in the same year.

Confirmation that Mary Ann Baker, the mother of the McNally children, was indeed Mary Ann Bugg is found in the baptism entry and the marriage and death certificates for her daughter Mary Jane McNally. These list the surname of Mary Jane's mother as being Baker, Brigg and Bug respectively.[12] As Mary Jane McNally and her two siblings were also listed on Mary Ann Burrows' death certificate, this is further confirmation that Mary Ann Burrows and Mary Ann Bugg and Mary Ann Baker were one and the same.

Mary Ann Burrows’ death certificate named ten children born to her second husband, John Burrows, although some were in fact born to Fred Ward (see Mary Ann Bugg - "Husbands" and Children). Mary Ann registered the birth of only one of these Burrows children: George Herbert Burrows in 1876. While she listed her surname as Burgess on George’s birth certificate, George himself reported on his marriage certificate that his mother’s name was Mary Ann Buggs.[13] Evidently Mary Ann was attempting to hide her true identity in the 1870s behind the surname Burgess.

Two of the Mary Ann Burrows’ other children – James Burrows (born in 1851 during her first stint with John Burrows) and Ida Margaret Burrows (born c1874 during her second stint with John Burrows) – were residing together at Hillgrove near Armidale in 1896 when Ida married. Both Ida’s marriage certificate and death certificate listed her mother as Mary Ann Bugg.[14] Also, their brother John Burrows (born 1853) listed his mother as Mary Ann Baker on his own marriage certificate in 1877[15]. And their youngest brother, Arthur, listed his mother as Mary Ann Buggs on his marriage certificate in 1918.[16] All of these children are listed on Mary Ann Burrows' 1905 death certificate.[5]

Clearly, Mary Ann Bugg did not die in 1867. Instead, she lived on as Mary Ann Baker/Brigg/Bugg/Boggs/Burgess/Burrows until her death in 1905. Seemingly, she hid the truth of her initial marriage to Edmund Baker and, to some extent at least, her connection with the notorious Captain Thunderbolt during these years.

Some Thunderbolt researchers continue to dismiss all of the above evidence showing that Mary Ann Bugg died as Mary Ann Burrows in 1905 simply because Mary Ann Burrows' death certificate stated that she was born in New Zealand and came to NSW when she was aged two.[3] But Mary Ann, of course, did not provide the information about her birthplace on her death certificate because she was dead by that time.

She did, however, provide information about her own birthplace when she registered the birth of her son George Herbert Burrows in 1876. Significantly, she reported that she was born in Gloucester, NSW (as was Mary Ann Bugg), not New Zealand.[13] This produces the response from the "non-believers" that Mary Ann Burrows could not be Mary Ann Bugg because Burrows listed her maiden surname as Burgess on the above-mentioned George's birth certificate. However, this argument ignores the fact that George himself listed his mother's maiden surname as Buggs on his own marriage certificate.[13]

Ultimately, we need only one piece of evidence to prove that Mary Ann Burrows was indeed Mary Ann Bugg: namely, one reference to one child listed on Mary Ann Burrows' death certificate showing that the child's mother carried the rare maiden surname Bugg instead of one of the tens of thousands of other possible surnames she could bear. As it turns out, we have many such references, and George's marriage certificate is merely one of them. But the clincher lies in the references to Mary Ann's son Frederick. For purposes of clarity, this evidence is repeated below:

- Frederick Wordsworth Ward aka Captain Thunderbolt and his lover Mary Ann Bugg had a child named Frederick Wordsworth Ward born in August 1868.[1 & 2]

- No further references to this child are found under the name Frederick Wordsworth Ward in the aftermath; however references have been found to a Frederick Wordsworth Burrows, who was the same age as Frederick Wordsworth Ward junior.

- A Frederick Burrows acted as the informant for the death certificate of his mother Mary Ann Burrows in April 1905 and reported that he was aged 36 at that time. This was the exact age that Thunderbolt and Mary Ann's son Fred junior would have been if he was still alive in April 1905 – to turn 37 in August 1905.[5]

- This Frederick Burrows, a horse trainer, died in 1937. At that time his brother, Arthur (who was also listed on Mary Ann Burrows' death certificate), reported that Fred's full name was Frederick Wordsworth Burrows.[4]

- This Frederick Wordsworth Burrows was the only person listed in the NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Online Death Indexes for the two centuries from 1787 to 1980 with the rare given name combination Frederick Wordsworth.

- Frederick Wordsworth Burrows' brother Arthur reported that Fred's parents were named John Burrows and Mary Ann Boggs (the latter being her maiden name, according to Arthur).[4]

- Arthur Burrows himself, when providing the information for his own marriage certificate, reported that his parents were named John Burrows and Mary Ann Buggs (the latter her maiden name, according to Arthur).[16]

Thus:

- Clearly, Fred and Arthur's mother carried the married surname Burrows and the maiden surname Boggs or Buggs.[4 & 16]

- Clearly, Frederick Wordsworth Burrows was the same person as Frederick Wordsworth Ward, son of Fred Ward aka Captain Thunderbolt and Mary Ann Bugg, but instead of calling himself Ward, he used his stepfather's surname Burrows.

- Clearly, Frederick Wordsworth Burrows' mother, Mary Ann Burrows, was the same person as Captain Thunderbolt's lover, Mary Ann Bugg.

- Clearly, Frederick Wordsworth Burrows' mother, Mary Ann Bugg, was the woman who died as Mary Ann Burrows in 1905.

Sources

[1] Birth Certificate: Frederick Wordsworth Baker [RBMD 1868/0016881]

[2] Baptism: Frederick Wordsworth Ward [RBMD Vol.161 No.1400]

[3] Mary Ann Bugg by Barry Sinclair - sighted 19 Jun 2011 [http://users.tpg.com.au/users/barrymor/Mary Ann Bugg.html]

[4] Death Certificate: Frederick Wordsworth Burrows [RBDM 1937/0011514]

[5] Death Certificate: Mary Ann Burrows [RBDM 1905/5831]

[6] See Mary Ann Bugg Timelines

[7] Obituary: Mary Ann Burrows in Mudgee Guardian 27 Apr 1905 p.13

[8] Birth Certificate: George Herbert Burrows [RBDM ref: 1876/0015712]

[9] Baptism: Mary Ann Bugg [RBDM ref: Vol. 23 No. 1494]

[9a] Empire 3 July 1865 p.5

[10] Baptisms: Mary Jane & Patrick Christopher McNally from Mudgee RC Register & Ellen McNally from Mudgee CE Register (details provided by Lynne Robinson)

[11] See Mary Ann Bugg - "Husbands" and Children)

[12] Baptism: Mary Jane McAnaly from Mudgee RC Register (provided by Mudgee historian Lynne Robinson); Marriage Certificate: Mary Jane McNally [RBDM QLD ref: 1882/7584]; Death Certificate: Jane McNally [RBDM QLD ref: 1897/3522]

[13] Birth Certificate: George Herbert Burrows [RBDM ref: 1876/0015712] & Marriage Certificate [RBDM ref: 1900/9103]

[14] Marriage Certificate: Ida Margaret Burrows [RBDM 1896/1179] & Death Certificate: Ida Margaret White [RBMD 1952/0011461]

[15] Gulgong Church of England Marriage Register: Marriage of John Burrows and Sarah Ann Lucas, 1877 [information provided by Mudgee historian, Lynne Robinson] backed up by Marriage Certificate [RBDM ref: 1877/3617]

[16] Marriage Certificate: Arthur Burrows [RBDM ref: 1918/9882]

No, Mary Ann did not have tuberculosis. Not according to the records, anyway. This claim is the result of a compounding error.

Most researchers have concluded – inaccurately – that Mary Ann Bugg was the woman named Louisa Mason who died in 1867 at Mrs Bradford’s house on the Goulburn River near Denman, NSW. The report of Louisa Mason’s inquest stated that she died of “Inflammation of the lungs”. Newspaper reports added that this was the result of “exposure”.

A Thunderbolt researcher who believed that Louisa Mason was Mary Ann Bugg evidently concluded that “inflammation of the lungs” was the phrase used at that time to describe tuberculosis. This is incorrect. The most common references to tuberculosis at that time were consumption and phthisis. What was then called “inflammation of the lungs” was what we now call pneumonia. Moreover, pneumonia is a condition that can readily result from exposure.

But this is all irrelevant, anyway, because the woman who died at the Goulburn River in 1867 was not Mary Ann Bugg but Louisa Mason, a different woman entirely (as discussed above).

Who was Louisa Mason?

Louisa Mason was the woman who “eloped” with Thunderbolt in October or early November 1867, the woman who later died at Mrs Bradford’s house on the Goulburn River near Denman, NSW. Many Thunderbolt writers have claimed that this woman was Mary Ann Bugg, and that Louisa Mason was one of Mary Ann’s nicknames. They are wrong.

The Muswellbrook correspondent for the Maitland Mercury reported: "On Saturday night last [23 Nov 1867], at about nine o’clock, information was brought to the police that Thunderbolt and his woman, Louisa Mason, commonly known as ‘Yellow Long’, were at Mrs Bradford’s on the Goulburn River, the latter in a dying state." [1]

The Empire had previously written that Thunderbolt "then proceeded to Segenhoe whence he took a half-caste girl who was living with a person well-known about here as Cranky Bob".[2] Another Maitland Mercury reference to the dead woman mentioned that her husband was a “free-selector residing in the Scone district”.[1]

These reports indicate that Louisa Mason came from the Segenhoe/Scone district and was the wife of "Cranky Bob". Civil records reveal that a woman named Louisa Jane Clark married Robert Michael Mason, a labourer from Rouchel near Scone, on 13 August 1867 at Muswellbrook. This is clearly the Louisa Mason, wife of Bob of Scone, mentioned in the above newspaper reports. The fact that Louisa Mason was also a “half-caste” woman partly explains the confusion between her and Mary Ann Bugg.

Louisa Mason was not Mary Ann Bugg, and Mary Ann never used the nickname Louisa Mason. In fact, one can't help feeling sorry for Mary Ann, not only because Thunderbolt ran off with Louisa Mason but because of what Mary Ann has had to endure in the aftermath. Hasn't it occurred to those determined to label her with the nicknames Louisa Mason and Yellow Long that Mary Ann probably had ill-feelings towards the woman? Surely, the last thing she would have wanted was to be known throughout the centuries by that woman's name!

Sources

[1] Maitland Mercury 28 Nov 1867 p.4 (two articles)

[2] Maitland Ensign quoted in The Empire 21 Nov 1867 p.8

Was "Yellow Long" one of Mary Ann Bugg's nicknames??

Astonishingly enough, no! This conclusion is the result of a compounding error.

Late in November 1867, the Muswellbrook correspondent for the Maitland Mercury reported: “On Saturday night last, at about nine o’clock, information was brought to the police that Thunderbolt and his woman, Louisa Mason, commonly known as Yellow Long, were at Mrs Bradford’s on the Goulburn River, the latter in a dying state”.[1]

Many Thunderbolt researchers have concluded – incorrectly – that Mary Ann Bugg was the woman who died at that time and, therefore, that Louisa Mason and Yellow Long (or Yellilong) were Mary Ann's nicknames. But Louisa Mason was someone else altogether and Yellow Long was that woman’s nickname, not Mary Ann’s.

While Mary Ann Bugg’s skin colouring was such that Yellow Long might have been an appropriate nickname, it was not her nickname. The only references in primary-source records to Yellow Long are references to Louisa Mason (as you can determine for yourself by searching the online newspapers).

Moreover, this sounds like the type of nickname given to someone who spent time living with Aboriginal people. Mary Ann, conversely, was sent to school in Sydney at the age of four so she could lead a “civilised life” (ironically, as it turns out!). When aged only fourteen, she married a white man and lived a “white” life until forced to take to the bush with Fred Ward in 1864. Her life circumstances were such that she was not only unlikely to bear such a nickname, she didn’t bear such a nickname.

Yellilong (as the nickname was sometimes written) seems to have originated in a 1960s attempt to make Mary Ann seem more Aboriginal.[2] However, the only primary-source reference to Yellow Long as a nickname for anybody is found in the Maitland Mercury reference.[1]

This is one of the many instances where a Thunderbolt writer made an error and later writers have repeated it. Unfortunately, the names Mary Ann Bugg and Yellow Long are now so closely entwined that it will be difficult to correct the secondary-source record. Future Thunderbolt writers who take the easy way out will no doubt continue to repeat this error.

Sources

[1] Maitland Mercury 28 Nov 1867 p.4

[2] Frederick Ward cuttings file at Mitchell Library, Sydney NSW